Martin’s Act

What is Martin’s Act?

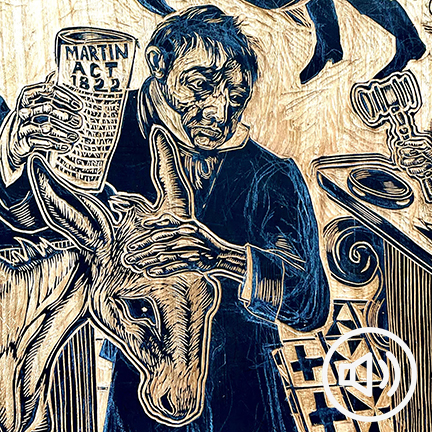

Well, its formal name is “An Act to Prevent the Cruel and Improper Treatment of Cattle,” but it is known as “The Cruel Treatment of Cattle Act,” and it was sponsored by the Irish politician Richard Martin (1754–1834), also known as “Humanity Dick,” and passed by the U.K. parliament and signed into law by King George IV on July 22, 1822. Martin’s Act, as the law was immediately called, is widely considered to be the first piece of animal welfare legislation passed by a modern representative body, and we think its bicentenary provides a wonderful opportunity to celebrate its passage and examine its legacy.

Richard Martin himself is a fascinating character, who lived in turbulent times. Revolutions rocked France and birthed the United States. The Atlantic slave trade and the expansion of European colonialism and imperialism, as well as rapid urbanization and industrialization, destroyed longstanding familial, national, and regional networks around the world. Yet this same period encompassed the emergence of a restless and ambitious middle class as well as unparalleled scientific discoveries and medicine; treatises on freedom and individual rights for men and women; and calls for representative government, the dignity of working people, and liberty from tyranny. From these, grew campaigns to emancipate Catholics, abolish slavery, form trades unions, expand democratic space, enlarge suffrage, end child labor, and establish public health.

Martin’s life also charted the stirrings of animal advocacy in the British Isles: William Hogarth’s satirical series The Four Stages of Cruelty (1751); Humphrey Primatt’s A Dissertation on the Duty of Mercy and Sin of Cruelty to Brute Animals (1776); philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s famous observations on animal suffering (1789); the radical vegetarianism of Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, and their circle; the passage of Martin’s Act itself; and two years later, the gathering in Old Slaughter’s Coffee House that created the Society for the Protection of Animals.

Why Martin’s Act?

Beyond the celebration of its bicentenary, Martin’s Act offers a useful reference point to consider legislative history, strategies, paradoxes, and challenges within Anglo-American common law, and the accompanying and competing political and social interests that mark it. It also serves as a point of reference to illustrate animal advocacy’s relationship with other social justice movements, and the parallels, convergences, or divergences with these movements over two centuries.

And there are other questions about the Act worth examining. As well as a champion for (some) animals, “Humanity Dick” was Ireland’s largest landowner, a hunter, and a meat-eater (at a time when there were “vegans,” albeit by other names). So, the Act also provides an opportunity to think about who was included and who wasn’t; about economic status, race, colonialism, and empire that the Act speaks to or ignores; and about the distinctions induced between animal welfare and animal rights, between livestock and “pets,” and between wild and domesticated animals. We might ask, indeed, whether the common law tradition and legislation offer the most lasting means by which to protect the natural world and the animals who share it with us. After all, ordinary people cared about animals, and proscriptions on harming certain groups of them existed, for millennia in societies all over the planet before the U.K. parliament passed Martin’s Act. An examination of that fact is the larger aim of chart2050.